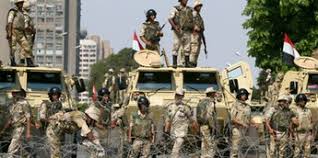

A recent survey by Afrobarometer shows that many Africans are increasingly open to military intervention in politics, especially when they believe elected leaders abuse power. The data highlights a worrying trend in public attitudes toward democracy across the continent.

The survey, conducted in 2024, indicates that 53% of Africans would tolerate military involvement if leaders “abuse power for their own ends,” while 42% believe the army should never intervene. Young Africans aged 18–35 are the most receptive, with 56% supporting military involvement under such circumstances, compared to 47% of older respondents.

Some of the strongest support comes from countries already under military rule, including Mali (82%), Guinea (68%), and Burkina Faso (66%). High levels of approval were also recorded in Niger (67%), Gabon (66%), Tunisia (72%), Côte d’Ivoire (69%), Tanzania (68%), Congo-Brazzaville (67%), and Cameroon (66%).

The survey reflects the context of recent political instability in the region. In West Africa, a coup attempt in Benin saw soldiers briefly remove President Patrice Talon before being stopped. Guinea-Bissau also experienced a military takeover in November 2025, just before disputed election results were due to be announced.

Public support for military intervention is often linked to dissatisfaction with civilian governments, political instability, security concerns, and economic hardship. In countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, years of jihadist violence and repeated coups have shaped the perception that the military may act more decisively than politicians.

Even in relatively stable countries like Tanzania, citizens appear to trust the military as a disciplined and corruption-free institution capable of stepping in if civilian governance fails.

Despite these trends, a significant minority in each country remains opposed to military involvement, reflecting ongoing concerns about authoritarianism, democratic erosion, and the potential risks of prolonged military rule.

The survey underscores the delicate balance between public frustration with political systems and the dangers of normalizing military intervention as a solution to governance challenges in Africa.