In a historic move that could redefine HIV prevention across Africa, South Africa’s Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) has approved the use of cabotegravir, a long-acting injectable drug that offers protection against HIV infection for up to eight weeks with a single shot.

The decision makes South Africa the first African nation to authorize this form of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a major public health milestone in a region that remains the global epicentre of the HIV epidemic.

According to UNAIDS, sub-Saharan Africa accounts for nearly two-thirds of the world’s 39 million people living with HIV, with young women and adolescent girls disproportionately affected.

“This is a breakthrough for the continent,” said Dr. Thembi Xaba, an infectious disease specialist at the University of the Witwatersrand. “For the first time, we have a prevention method that doesn’t rely on daily pills or condoms — and that gives women more control over their health.”

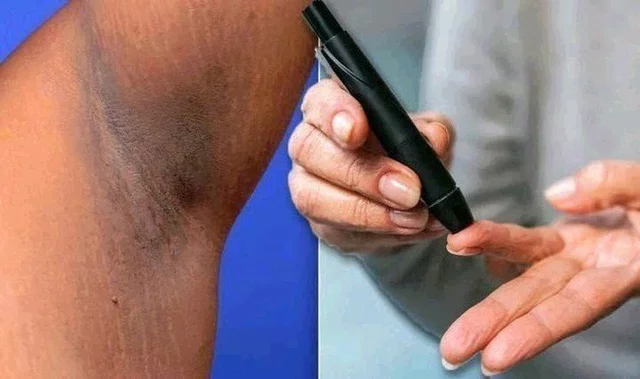

Cabotegravir, marketed as Apretude, is a long-acting injectable antiretroviral developed by pharmaceutical company ViiV Healthcare. Once administered intramuscularly every two months, it maintains protective levels of the drug in the bloodstream, blocking HIV from entering human cells.

Clinical trials conducted in Africa, the United States, and Latin America demonstrated remarkable efficacy, showing that the injection reduced HIV risk by up to 89% compared to traditional daily PrEP tablets.

This advancement particularly benefits people who face stigma, adherence challenges, or limited access to consistent medication.

“Many women in rural and low-income communities find it difficult to take a pill every day without their partners knowing,” said Dr. Xaba. “An injection every two months offers discreet, powerful protection.”

South Africa’s approval is expected to pave the way for regional adoption in countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Nigeria, where HIV prevention efforts face similar cultural and logistical barriers.

Health officials in Tanzania have already expressed optimism that regulatory review will follow. The Tanzania Medicines and Medical Devices Authority (TMDA) confirmed that it is studying data from South Africa’s approval process to consider potential rollout options.

“We are closely monitoring developments,” said Dr. Salma Abdallah, TMDA’s head of clinical trials. “If safety and cost factors align, cabotegravir could be a critical addition to our HIV prevention strategy.”

Despite its promise, access remains a concern. The injectable PrEP currently costs around USD 250–300 per dose in Western markets — far beyond the budgets of most African health systems.

However, the Global Fund, PEPFAR, and UNAIDS have entered negotiations with ViiV Healthcare and the Medicines Patent Pool to allow generic manufacturing for low- and middle-income countries.

If successful, these deals could bring the price down to under USD 20 per dose, enabling widespread distribution through public health facilities.

“We cannot let price stand between Africans and innovation,” said Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “This jab has the power to change lives — especially for young African women, who remain the face of new HIV infections.”

Public health experts warn that scientific innovation alone is not enough. For cabotegravir to succeed, countries will need strong awareness campaigns, supply chain systems, and training for healthcare workers.

Civil society groups in South Africa and Kenya have already launched pilot education programs targeting adolescent girls, sex workers, and truck drivers — populations at higher risk of infection.

“Prevention tools only work if people know about them and trust them,” noted Prof. Daniel Mushi, a Tanzanian public health researcher. “Our approach must be community-driven and respectful of cultural dynamics.”

South Africa’s move comes as the world continues its decades-long battle against HIV/AIDS — a disease that has claimed more than 35 million lives since the 1980s.

The injectable represents not just a new medical tool but a symbol of hope and autonomy for millions of Africans.

“For many, this jab means freedom — freedom to love, to plan families, and to live without fear,” said Dr. Xaba. “It’s the closest we’ve come to stopping HIV before it starts.”