Madagascar’s military leader Colonel Michael Randrianirina announced on Wednesday that he will soon be sworn in as president, following a swift and dramatic coup that ousted embattled President Andry Rajoelina after weeks of youth-led protests and deepening political unrest.

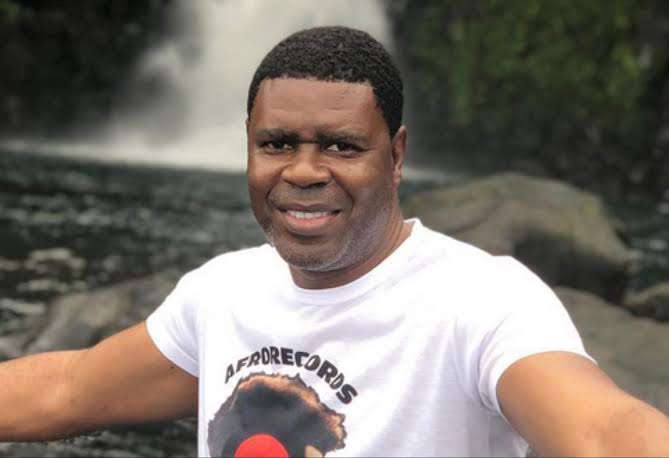

The 45-year-old colonel, who once served in the same elite military unit that helped Rajoelina seize power in 2009, now finds himself leading Africa’s largest island nation through one of its most turbulent transitions in decades.

“We took responsibility yesterday,” Randrianirina told reporters in Antananarivo. “We will be sworn in soon.”

Randrianirina, previously a commander in the elite CAPSAT unit, declared the dissolution of all national institutions except the National Assembly, saying the military had “acted in the people’s interest” to end political stagnation, worsening poverty, and a leadership crisis fueled by mass youth unemployment and corruption.

The coup followed months of public anger over frequent power blackouts, fuel shortages, and soaring food prices — frustrations that culminated in massive youth-led protests across the country. Security forces reportedly refused to suppress demonstrators after several units broke ranks, joining calls for the president’s resignation.

The High Constitutional Court later invited Randrianirina to assume the presidency temporarily, pending a transition period expected to last up to two years, during which a transitional government will prepare for new elections.

Ousted President Andry Rajoelina, 51, fled Madagascar on Sunday aboard a French military aircraft amid reports of a split within his security circle. Diplomatic sources told Reuters he is currently in Dubai, having declared he remains the country’s “legitimate president.”

Rajoelina’s government collapsed after the National Assembly impeached him for “abandoning the presidency” and “violating the constitution.” Despite his flight, he released a recorded statement online condemning the military takeover.

“This is not the will of the Malagasy people but the work of opportunists in uniform,” Rajoelina said. “I will not resign.”

Rajoelina himself rose to power through a 2009 coup, backed by the same CAPSAT unit now led by Randrianirina. His administration had long faced accusations of authoritarianism and corruption, with critics pointing to his failure to deliver on promises to improve living standards.

The recent unrest was largely driven by Madagascar’s youth, who make up more than 60% of the population. Many demonstrators say they feel betrayed by successive leaders who have failed to create jobs or address inequality.

“We have no work, no electricity, no future,” said 20-year-old student Noro Raharimanana, one of the protesters in Antananarivo’s Independence Avenue. “The soldiers listened to us when the politicians would not.”

The demonstrations, initially peaceful, grew nationwide, with students, transport workers, and teachers joining in. As state control weakened, opposition groups called for an “interim civilian-military alliance” to restore stability.

The African Union (AU), United Nations, and Southern African Development Community (SADC) have all condemned the coup, urging a swift return to constitutional order. AU Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat called the takeover “a serious setback for democracy” and announced that Madagascar faces suspension from AU activities pending dialogue with the junta.

France, Madagascar’s former colonial power, issued a cautious statement urging restraint and respect for human rights. “We call on all parties to prioritize peace and the welfare of the Malagasy people,” said a French Foreign Ministry spokesperson.

In contrast, some African analysts see the coup as a symptom of growing frustration across the continent with entrenched leadership and inequality.

“Like coups in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso, this reflects a generational demand for accountability,” said Dr. Alphonse M’baye, a political analyst at the Institute for African Governance. “But military takeovers rarely deliver long-term solutions.”

Madagascar, home to nearly 30 million people, remains one of the world’s poorest countries. Three-quarters of its citizens live below the poverty line, according to the World Bank, and GDP per capita has fallen by nearly half since independence in 1960.

The country’s fragile economy, heavily dependent on agriculture and tourism, has been battered by political instability and climate-related disasters, including severe cyclones and droughts.

Randrianirina has pledged to stabilize the nation’s energy sector, reform public institutions, and fight corruption during the transition. However, critics warn that without a clear roadmap or civilian participation, the coup could deepen divisions.

“We will not repeat the mistakes of the past,” Randrianirina said. “Our mission is national renewal — not personal gain.”

Randrianirina’s upcoming swearing-in ceremony is expected within days, likely at the Iavoloha Presidential Palace under tight security. He has hinted that the transitional government will include technocrats, civil society members, and select lawmakers to ensure inclusivity.

Despite assurances, uncertainty remains high. Many Malagasy citizens are weary of recurring coups — this being the fourth since 1972 — and fear history may repeat itself.

As one Antananarivo shopkeeper, Fanja Rakotondrabe, put it:

“Every time there’s a coup, they promise change. But the poor always stay the same.”