In Duekoue, a small town in western Ivory Coast once scarred by one of the country’s bloodiest massacres, a quiet but powerful movement is reshaping the meaning of peace — one wedding at a time.

After more than a decade of mistrust and ethnic division, locals are turning to what they call “reconciliation marriages” — unions between members of rival ethnic communities once torn apart by political violence.

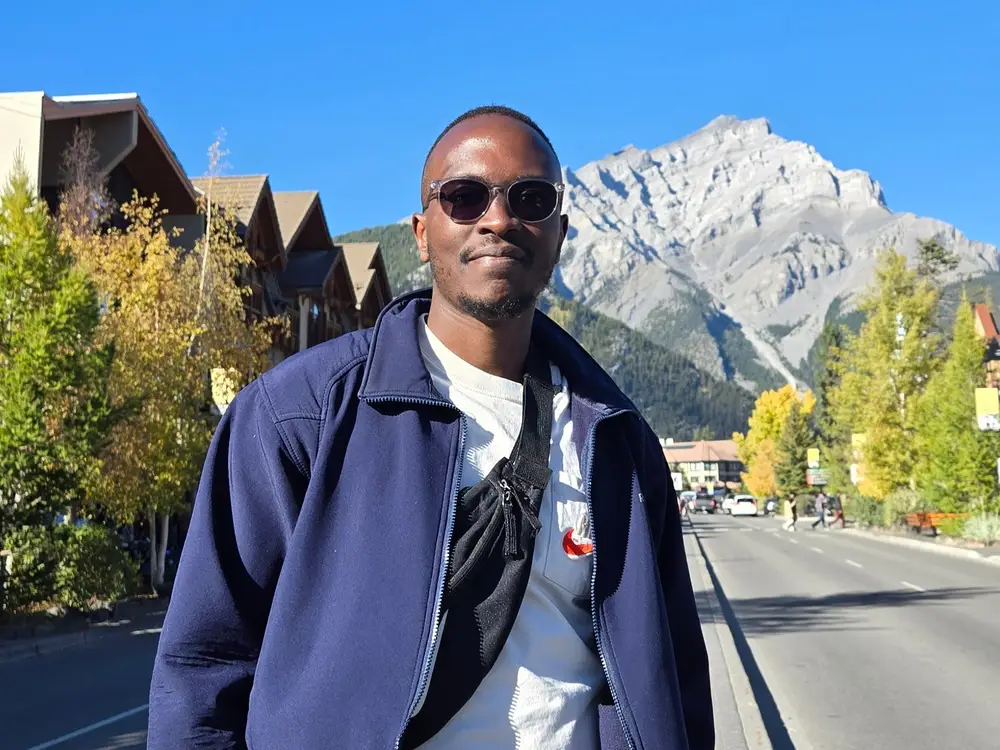

At the heart of this movement are couples like Matinez Pode, from the Guere ethnic group, and Elisabelle Kouadio Ahou, a Baoule woman. The two communities were bitter enemies during the 2010–2011 post-election crisis, which claimed thousands of lives and left deep wounds across the country.

Despite fierce objections from their families, Pode and Kouadio married in 2012, barely a year after Duekoue’s darkest days, when pro-government forces loyal to then-President Alassane Ouattara were accused of killing hundreds of people, mostly Gueres.

Human Rights Watch reported at the time that several hundred civilians were massacred in and around Duekoue, as revenge attacks followed the disputed election that saw Ouattara replace Laurent Gbagbo, who refused to concede defeat.

“Both our families tried to stop us,” Pode recalls. “But we were determined to live together and prove that love can heal what hate destroyed.”

Today, the couple walks hand in hand near the green hills outside Duekoue, their union a living symbol of hope.

Behind this wave of reconciliation is Limpia, a local nonprofit dedicated to peacebuilding and social healing.

Since 2013, Limpia has helped organize community dialogues, youth programs, and cross-ethnic weddings — including counseling, legal aid, and family mediation.

Its director, Alexis Kango, says the idea of mixed marriages grew from the realization that political agreements alone cannot mend a fractured society.

“These marriages will create grandchildren and great-grandchildren who will share language, land, and family ties,” Kango says. “That is how real peace is built — through generations.”

As Ivory Coast prepares for another tense presidential election this Saturday, Limpia is planning a mass wedding for 10 new couples early next year, hoping to strengthen bonds before political tensions rise again.

Duekoue, located about 400 kilometers west of Abidjan, lies in the country’s cocoa-rich region, where competition for land has long fueled ethnic and political conflict.

The area saw some of the worst violence during Ivory Coast’s civil wars, as communities clashed along political and regional lines.

During the 2010–2011 crisis, Gueres — mostly supporters of former President Gbagbo — were targeted by fighters aligned with Ouattara, a Dioula from the north. Many homes were burned, and entire families fled.

Though peace has largely returned, memories of the massacre still shape everyday interactions. Some survivors say reconciliation has been slow, with justice for war crimes still incomplete despite government amnesties issued in 2018.

President Ouattara, now seeking a fourth term in office, described those amnesties as “a measure of clemency for national unity.” But rights groups argue they allowed perpetrators of atrocities to evade accountability.

For residents of Duekoue, reconciliation is taking root not in courtrooms but in homes, schools, and wedding halls.

Souleymane Taha, an ethnic Guere who married his Dioula wife, Matoma Doumbia, in 2019, says he has seen the power of these unions firsthand.

“Mixed marriages bring peace to communities,” he says. “When families eat together and raise children together, they stop seeing each other as enemies.”

Taha and his wife live in a predominantly Dioula neighborhood, where their interethnic family is now regarded as a bridge between communities. Even during moments of political tension, he says, their neighbors have always protected them.

The International Crisis Group has warned that Ivory Coast has not experienced a completely peaceful election since 1995, and fears persist that political rivalries could again inflame ethnic divisions.

But in Duekoue, Limpia’s work offers a rare sign of optimism.

Kango says his organization will continue to promote peace through love, dialogue, and shared community projects — even if progress is slow.

“Every wedding is a new treaty between two families,” he says. “And every child born from those unions is a victory for peace.”

As the nation braces for another election season, couples like Pode and Kouadio represent a different kind of campaign — one for unity, not power.

Their story is a reminder that reconciliation is not signed in political offices, but written in everyday acts of courage, forgiveness, and love.

“We cannot change the past,” Kouadio says softly. “But we can raise children who will never repeat it.”