As glaciers continue to melt at an alarming rate due to climate change, the future of glacier tourism a vital industry in the Alps and beyond—is now at a crossroads. Millions of tourists visit glaciers each year, fueling local economies and supporting mountain communities. But with glaciers retreating, some destinations may soon vanish entirely.

However, experts say this doesn’t have to mean the end of tourism in glacial regions. In fact, the changing landscape could offer new kinds of tourism experiences from scientific education and climate awareness to virtual adventures.

In Switzerland, glaciers have long attracted visitors and inspired the development of ski resorts, mountain huts, and infrastructure like the Jungfrau Railway, which was built in 1912 to access the glaciers of the Bernese and Valais Alps.

But now, rising temperatures are melting the ice, thawing permafrost, and destabilizing the ground beneath roads, ski lifts, and cable cars. Activities like ice-cave visits and mountaineering are becoming more dangerous or impossible in some areas.

In response to the crisis, the United Nations has declared 2025 the International Year of Glacier Preservation.

Dr. Emmanuel Salim, a glacier tourism expert and researcher at the University of Lausanne and University of Toulouse, believes the industry must adapt to survive. In a recent study, he outlines three innovative approaches to help glacier tourism thrive—even as the ice disappears:

Instead of focusing only on beauty, geotourism teaches visitors about the Earth’s history and geology. Glaciers can become open-air classrooms, showing the real effects of climate change.

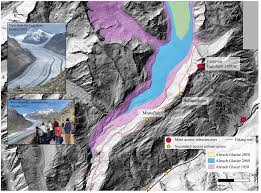

A great example is Switzerland’s Aletsch Glacier, the largest glacier in the Alps and part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Environmental groups like Pro Natura already lead educational tours there, with apps and signs that explain how the glacier is shrinking—and why it matters.

“Even if the glacier melts, people can still come to learn about geology and climate,” says Dr. Salim.

The second approach is dark tourism visiting places connected to tragedy or loss. This could apply to glaciers like France’s Mer de Glace, which saw 450,000 visitors in 2024. Experts say many tourists are already going to see the glacier “before it’s gone.”

In the future, sites like Mer de Glace could become memorials to lost glaciers, helping visitors understand the human impact on nature. This mirrors examples like Okjökull in Iceland, which became the first glacier to receive a memorial plaque, and Switzerland’s Pizol Glacier, which also vanished due to warming.

“It’s not just about the glacier,” says Salim. “It’s about the message it leaves behind.”

For places where the ice is already disappearing, virtual reality could bring it back. Tourists can use VR headsets to see what glaciers used to look like—and how they’ll change in the future.

This is already being tested at Morteratsch Glacier** in Switzerland. At the Diavolezza Valley cable car station, visitors can experience the glacier’s past, present, and future—from 1875 to 2100—through immersive VR technology.

“It’s a powerful way to connect people to a disappearing world,” says Salim.

These ideas—geotourism, dark tourism, and virtual experiences—can be used together. Tourism operators can choose the best mix depending on the location and audience. The key is to adapt early and build a long-term plan.

“The idea of the glacier can still survive,” says Salim, “even if the ice itself doesn’t.”

Glacier tourism is economically vital for mountain regions.

Glaciers are rapidly disappearing, threatening jobs and infrastructure.

New forms of tourism can educate, inspire, and preserve memory.

This transition will help **communities stay resilient** in the face of climate change.

The melting of glaciers is not just a climate warning—it’s a wake-up call for how we experience nature. With creative thinking and responsible tourism, we can honor the glaciers, support local economies, and build a new future for travel in the Alps and beyond.