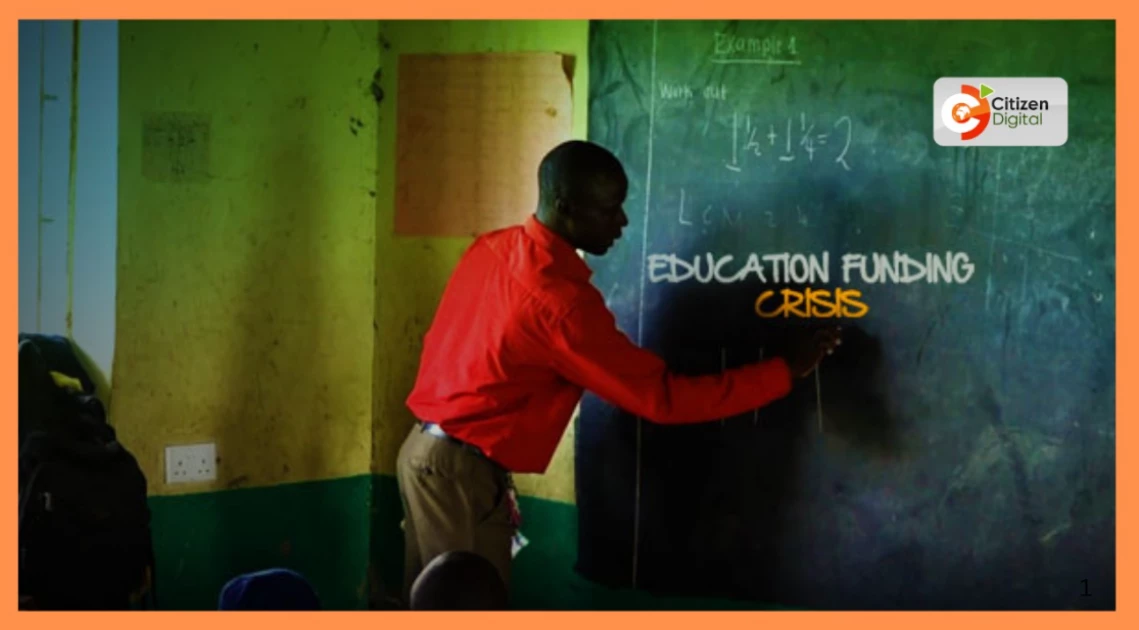

Kenya’s once-proud dream of free education — a promise that opened doors for millions of children — is quietly crumbling.

From the days of “Maziwa ya Nyayo” and free primary schooling under the late Presidents Daniel arap Moi and Mwai Kibaki, to today’s mounting school fees and shrinking government support, many parents and educators are asking: what happened to free education?

When the government first introduced the Free Primary Education (FPE) and later the Free Day Secondary Education (FDSE) programs, they were hailed as historic victories for equity.

The initiatives opened classrooms to children who had never dreamt of schooling — especially in rural and low-income communities.

But two decades later, that promise appears to be fading. Classrooms are emptier, and schools that once thrived on government support are struggling to stay afloat.

In early 2025, the Ministry of Education admitted to slashing the annual capitation grant — the government’s contribution per student under the FDSE programme — from KSh 22,244 to about KSh 12,000 per learner. Officials cited rising enrollment and a stagnant education budget capped at around KSh 65 billion.

However, school principals across the country say the situation is even worse. Many claim they have received as little as KSh 8,818 per student for the first term of 2025 — far below what is required to run schools effectively.

The result? Delayed salaries for support staff, shortages of learning materials, and schools quietly passing additional costs to parents — the very people free education was meant to protect.

“If former President Daniel arap Moi woke up today,” one headteacher quipped, “he’d find that his free milk programme has been replaced by empty desks.”

The nostalgia runs deep. Moi’s “Maziwa ya Nyayo” milk program not only nourished schoolchildren but also symbolized government commitment to education.

When President Kibaki took office, he carried that spirit forward with free primary education, lifting millions out of illiteracy.

Now, parents say the burden is shifting back onto them. Many are being asked to pay for school maintenance, exams, and even basic learning materials. For low-income families, these hidden costs are unaffordable — and children are quietly dropping out.

Government officials point to budget deficits and competing priorities. Yet, Kenyans continue to witness heavy spending on political rallies, early campaign mobilization, and lavish state events.

Critics argue that this shows a lack of political will to protect one of Kenya’s most transformative social programs.

“Why slash school funding when we could cut unnecessary political bursaries and allowances?” asks one education analyst. “If we can’t protect education, what exactly are we building as a nation?”

The consequences are already visible. In some rural schools, classrooms that once hosted 50 learners now have fewer than 20. Parents face painful choices: feed their families or pay school fees. Teachers report rising absenteeism and declining morale.

Education experts warn that if the funding shortfall persists, Kenya risks undoing decades of progress. “When a child misses education, they don’t just lose lessons,” one headteacher said. “They lose their future.”

Education has always been Kenya’s equalizer — the bridge between poverty and opportunity. The erosion of free education is more than an economic issue; it’s a moral one.

If we continue on this path, Kenya may soon become a country where tuition decides destiny — where the children of the rich inherit opportunity and the poor inherit despair.

We must return to the ideals that shaped our past: education as a right, not a privilege. Free education should mean truly free — funded, accessible, and sustainable.

Until that day, the empty desks in our classrooms will stand as silent witnesses to a generation being left behind.